|

||||

|

by John Engstrom

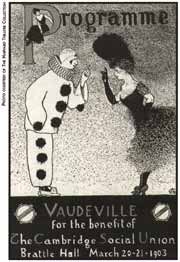

The Brattle Theatre at historic Brattle Hall inspires a kind of nostalgia verging on worship. For anyone who has browsed through the building's subterranean retail shops, or been introduced to Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Francois Truffaut, or Jean-Luc Godard in its 250-seat theatre, that is the sine qua non of the structure, the Brattle is full of memories, part of our collective unconscious. A century ago its Victorian founders envisioned a multifarious cultural center, combining theatre, lectures and meetings. In a curious way, even through its incarnations over the years as a legitimate theatre and a haven for art-repertory cinema, the Brattle Theatre's connection to these early goals has stayed remarkably close. But to chart the history of the Brattle one must begin in the years following the Civil War. In the late nineteenth century, American communities began to set up "social unions," organizations where restless young men and women might combine entertainment with moral and intellectual self-improvement. The Cambridge Social Union, founded in January 1871, and located at Lyceum Hall at 1400 Massachusetts Avenue (now the site of the Harvard Cooperative Society), was immediately popular. One of the cofounders of the union was the staunch Reverend Samuel Wadsworth Longfellow (brother of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose august Federal mansion still stands a few doors up prestigious Brattle Street). By 1889 the union had sufficient wherewithal to purchase a lot for $9,000 on which to build a multipurpose space and to hire the prestigious Cambridge architectnral firm headed by Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow (nephew of the poet and of the Reverend Samuel, cousin of Alice, who was later to perform amateur theatricals there) to draft plans for the proposed Brattle Hall. Early photographs of the completed structure show a simple, unpretentious Queen Anne-style edifice with a gambrel roof of gradual pitch; clapboards on the outside; and, framing and sheltering the front door, a porte cochere or passageway where horse-drawn buggies could pull up, deposit their passengers, and drive off. Inside, the building was essentially one room, 46 by 40 feet, and its stage was 20 feet deep and 45 feet long. "Handsomely decorated in color and excellently ventilated," a contemporary news accountsaid. "In the basement are dressing and cloak rooms." Nine years after the gala opening of Brattle Hall, on 27 January 189O, the building received the first of several significant alterations. More seats were added, an obstructive chimney removed, and the stage given an additional 20 feet of depth, which meant that actors could leave the stage without leaving the building.

In January 1891, the Cambridge Dramatic Club, rechristened the Cambridge Social Dramatic Club, started giving Saturday evening performances in Brattle Hall, which it rented from the Social Union for its performances of Restoration classics, Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, and other staples, as well as more obscure plays. One of the latter, put on at the Brattle during the 1912-13 season, was titled The New Lady Bantok; or, Fanny and the Servant Problem. The part of Lord Bantock was played by T.S. Eliot. Another distinguished member of the theatre troupe was Harvard professor George Pierce Raker, the renegade playwriting teacher who later defected to Yale. With the arrival of the depression in 1929, membership in the club sharply decreased, and ceased to be a viable source of revenue for the union. (The club folded in 1950.) The union rented Brattle Hall to other tenants, including the Christian Science and Lutheran churches and the Cambridge Police Department, which used the space as a gymnasium. In 1938, the union became the Cambridge Center for Adult Education which continues to this day at the Brattle House next door. Throughout the 1930s and '40s the house was hired by a series of professional theatre companies and was the scene in August 1942 of the U.S. premiere of Paul Kobeson in Othello, opposite Uta Hagen and Jose Ferrer. In 1946, a small but significant advertisement appeared in the Harvard Crimson. The ad was placed by Jerome Kilty, a Harvard student, Air Force veteran, and actor. Kilty found the Harvard dramatic societies excessively "clubby" and was having difficulty getting roles in their productions. His ad, he recalls said, "Any veteran who would like to start a new theatre group come to see me at Eliot House, C31." About 70 people showed up at the meeting, and the new group named itself the Veterans' Theatre Workshop. It began with a staged reading of Hamlet, directed by Kilty and featuring as Polonius Harvard graduate student John Simon, who is now the drama critic of New York magazine. With the approach of graduation, members of the group discussed the possibility of forming their own company independent of Harvard. While all agreed with this goal, they realized that a space was needed. At the same time, the Cambridge Social Union announced that it was selling Brattle Hall at an auction. In 1948 Thayer Frye Hersey, the wealthy father of David Hersey, a Veterans' Theatre Workshop member who later became famous as a character actor named Thayer David, purchased the building for the group, which renamed themselves the Brattle Theatre Company. In 1949, when Thayer Hersey became ill, Bryant Haliday, another member of the Brattle core group, bought the building back from him.

Among the big names who played the Brattle during those years were Winifred Lenihan, creator of the title role of C.B. Shaw's Saint Joan, who repeated her performance at the Brattle in 1948; Irish actress Sara Allgood; Cyril Ritchard; Jessica Tandy and Hume Cronyn; Luise Rainer; and Zero Mostel, who starred in the company's last production, Moliere's The Doctor in Spite of Himself. One salutary aspect of the Brattle Company was its policy of hiring actors who were blacklisted during the U.S. government's political witch hunts of the 1950s. Blacklisted guest stars at the Brattle included Mostel, Anne Revere,and Sam Jaffe, of Ben Casey fame. But a roll call of glamorous names is misleading since the reputation of the Brattle Company rested (from all accounts) not on any star system but on solid ensemble performances of classics, from Shakespeare to Congreve to Chekhov, and the flexibility of its actors. Shortly after the company folded in 1952, from a combination of financial losses and "artistic differences," several of the actors went on to establish themselves in professional theatre, notably Jerome Kilty, Albert Marre, Robert Fletcher, Thayer David, Nancy Marchand, and stage designer Robert O'Hearn. Locked into sequential runs of each play, the company never instituted a policy of alternating repertory. But in a period when the concept of regional theatre was virtually unknown in America as was the ensemble principle, and state subsidy for theatre was nonexistent, the Brattle group broke fresh ground. In the 1950s, the Brattle shifted from being a live-performance venue to one primarily associatcd with film. Its new identity was in a way an outgrowth of the theatre company; Bryant Haliday teamed up with fellow Harvardian Cyrus Harvey, Jr. to convert the theatre into a cinema.

However, the most innovative thing about the "new" Brattle was not its machinery but its programming. Harvey, a former Fulbright scholar at the Sorbonne in Paris, was influenced by the precedent- setting repertory he'd seen at the Cinematheque, then under the direction of Henri Langlois. To his programming at the Brattle he brought a breadth of taste, a curator's zeal, and an internationalism that embraced not only American but foreign films. In February 1953, while other local theatres showed Disney's Peter Pan and Esther Williams in Million Dollar Mermaid, the "new" Brattle screening series kicked off with a German import, Carl Zuckmayer's Captain from Kopenik. Admission was 80 cents. The run was announced as open-ended. The eclectic opening season set the tone for what followed: My Little Chickadee with W.C. Fields and Mae West; Hitchcock's The Lady Vanishes; the John Grierson documentaries Song of Ceylon and Night Rain; a triple bill of Jean Cocteau's Orphee, a nature documentary about France's Black River, and a film on the Renaissance painter Fra Angelico; The Blue Angel and Eisenstein's Ivan the Terrible. Throughout the 1950s and '60s, the Brattle programs under Harvey and Haliday conctinued to put foreign films in offbeat juxtapositions with American classics. They revived public interest in the then-neglected films of Humphrey Bogart with a week-long Bogart series, which became an annual tradition at Harvard exam time. In 1954-55, the team expanded their operations by purchasing New York's 55th St. Playhouse, and founded Janus Films, Inc.-for many years the U.S. distribritor of such auteurs as Jean-Luc Godard, Frederico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Francois Truffaut, and Ikira Kurosawa. Among other coups, Harvey personally accepted the Best Foreign FiIm Oscar for Bergman (for The Virgin Spring) in 1961. But by the mid-'6Os, many of the filmmakers Harvey and Haliday had discovered and nurtured under the Janus aegis started defecting to Hollywood, notably Bergman and Truffaut. The company folded in 1966, with a thousand dollars in the bank. Ten years later, Harvey sold the Brattle lease to Sari Abul-Jubein of G & A Associates, who physically altered the theatre (taking out the balcony and about 50 seats) with an eve toward increasing retail space, while Bill Holodnak maintained the Brattle's high quality of repertory programming. The early '8Os were a time of retrenchment for the repertory ideal, with houses all over the country and in the Boston area closing one after the other. But the Brattle acquired a new look in 1982 when Susan Pollack started leasing the theatre. With her husband, JD, who had publicized films for the Orson Welles Cinema, Pollack upgraded the interior--installing a new screen and sound system, recarpeting the floors and restoring the balcony. The Pollacks briefly revived the Brattle as a legitimate theatre with a performance series, which kicked off in the fall of 1984 with a String quartet and the premiere of monologist Spalding Gray's Travels Through New England.

Despite some forays into theatre, though, the Pollacks were faithful to the tradition of the Brattle as a repertory cinema. When their successors Marianne Lampke and Connie White, who had helped the Pollacks with performance bookings, took over the Brattle Theatre in 1986 they brought with them a commitment to independent and repertory cinema--and newly struck and restored prints. Their company, Running Arts, programming features kaleidoscopically changing "vertical" series with different films almost every night: Film Noir on Mondays and author readings, sponsored by Wordsworth Books, and independent filmmaking on Tuesdays. One night a week is designated for foreign directors, and weekends are filled with Hollywood classics, premieres and special events. In its one hundred years of existence the Brattle has been put to uses that probably would have surprised Reverend Longfellow and the cofounders of the Cambridge Social Union. But even Longfellow would have to admit that the original goal of the founders of Brattle Hall, combining entertainment and intellectual enlightenment for and by the young, has stayed remarkably intact. John Engstrom is a freelance writer who lives in Dorchester, MA. His articles have appeared in the Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, Horizon Magazine, and many other publications. He has been a staff member at Plymouth Plantation and currently works for the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. His father, Elmer Engstrom, did the translation for the last production of the Brattle Company, The Doctor in Spite of Himself, in 1952. This article was writen in 1990 for the Brattle Theatre's 100 year anniversary. |

||||

|

©Copyright 2001 Brattle Film Foundation. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. Questions or Comments? Contact Us. |

Live

entertainment was not as accessible to Cantabridgians at the turn

of the century as it would be after 1912, when the subway line began

running from Cambridge to Boston. As a result, local amateur theatricals

enjoyed a considerable following.

Live

entertainment was not as accessible to Cantabridgians at the turn

of the century as it would be after 1912, when the subway line began

running from Cambridge to Boston. As a result, local amateur theatricals

enjoyed a considerable following. A

history of the Brattle easily reads like an exercise in starry-eyed

name-dropping, since so many distinguished actors and actresses

were associated with it. This was particularly true of the tenure

of the Brattle Theatre Company, which occupied the theatre from

1948 through 1952 and often jobbed in stars to gussy up its casts

(and boost box office sales).

A

history of the Brattle easily reads like an exercise in starry-eyed

name-dropping, since so many distinguished actors and actresses

were associated with it. This was particularly true of the tenure

of the Brattle Theatre Company, which occupied the theatre from

1948 through 1952 and often jobbed in stars to gussy up its casts

(and boost box office sales). Harvey

and Haliday tore out old seats, repainted the walls, and added new

upholstery and a "Translux" rear projection system. The

projector beams its light at a small mirror angled at 45 degrees,

which throws a reverse image on the screen. While the projectionist

sees the image backward, the audience sees it in correct perspective.

To this day, the Brattle is one of the few U.S. cinemas to use this

system with two Peerless projectors from the '5Os that burn carbons

rather than electric bulbs.

Harvey

and Haliday tore out old seats, repainted the walls, and added new

upholstery and a "Translux" rear projection system. The

projector beams its light at a small mirror angled at 45 degrees,

which throws a reverse image on the screen. While the projectionist

sees the image backward, the audience sees it in correct perspective.

To this day, the Brattle is one of the few U.S. cinemas to use this

system with two Peerless projectors from the '5Os that burn carbons

rather than electric bulbs.